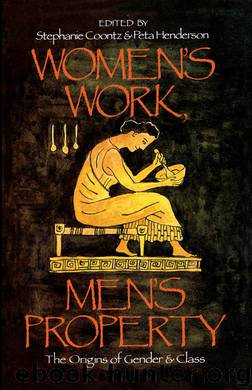

Women's Work, Men's Property: The Origins of Gender and Class by Stephanie Coontz & Peta Henderson

Author:Stephanie Coontz & Peta Henderson [Coontz, Stephanie]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Verso Books

Published: 2016-02-29T23:00:00+00:00

The Development of a Sexual Division of Labour

The earliest human societies were undoubtedly small, loosely organized groups whose survival depended upon generalized sharing and cooperation as well as on flexible living and work arrangements.9 As Leibowitz argues in her contribution to this volume, an informal division of labour by sex probably developed in populations that adopted projectile weapons, or any other technology allowing specialization between hunting of big game and collecting. With smaller numbers of hunters pursuing game over long distances, and with the possibility of spontaneous hunting as soon as animal tracks were sighted (without the time-consuming collective preparation required by the ‘surround’), it was more convenient, usually, for hunters to be males. This was not due to differences in size, strength or aggressive capacity but to the inadvisability of risking childbearers in such ventures or of requiring mothers, who were likely to have a nursing child beside them for a period of up to four years,10 to drop the child, without prior arrangement, in the interests of a speedy pursuit of game. Despite the wide variability in the sexual division of labour and in the valuation of male and female tasks, there is a clear cross-cultural pattern in primitive societies whereby women perform subsistence, manufacturing and processing tasks that are closer to home base, while males take on more long-distance and risky pursuits that require sudden, sustained and unplanned periods of activity and are thus difficult to reconcile with pregnancy or nursing.11

We want to be very clear about what this division of labour did and did not imply. It did not mean that men were more aggressive or powerful than women, since hunting is not normally an aggressive act in foraging societies,12 and disputes are rarely settled by the use of weapons but rather by individual fission13 or by involving the whole community in the argument until a solution is reached.14 Indeed, women frequently show themselves every bit as capable of aggressive behaviour as men15. Contrary to Brown and Parker and Parker,16 moreover, it did not mean that women’s tasks were dull or, because compatible with frequent breaks for nursing, less skilled than men’s, nor that they were considered so by members of society. Draper17 has shown that the gathering expeditions of !Kung women require great skill and are eagerly greeted by the entire camp on their completion. Briggs18 has argued that even among the Eskimo, where the division of labour results in a preponderantly male contribution to the diet, female work is not devalued. In most gathering societies, both male and female tasks are celebrated, and individuals of both sexes gain respect by excelling in their work. The frequency of female representations in Palaeolithic and Neolithic art work suggests that this was the case then as well.

Nor did the division of labour make women immobile or sedentary. In some West African societies women have carried on trade over considerable distances, in many hunting-gathering societies childless women may accompany men on the hunt, and in nomadic groups women move readily along with the men and do their fair share of the work.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

Born to Run: by Christopher McDougall(7127)

The Leavers by Lisa Ko(6948)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(5416)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5372)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(5197)

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini(5180)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4313)

Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber(4190)

Never by Ken Follett(3957)

Goodbye Paradise(3810)

Livewired by David Eagleman(3775)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3399)

A Dictionary of Sociology by Unknown(3085)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(3074)

The Social Psychology of Inequality by Unknown(3031)

The Club by A.L. Brooks(2926)

Will by Will Smith(2920)

0041152001443424520 .pdf by Unknown(2846)

People of the Earth: An Introduction to World Prehistory by Dr. Brian Fagan & Nadia Durrani(2739)